This week, ministers announced new plans to embed “grit” into the school day. As part of the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill, pupils will be taught how to “persevere when things get tough”, with character-building lessons, behaviour hubs and sessions to tackle anxiety and low mood.

In a joint letter in The Telegraph, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson and Health Secretary Wes Streeting explained:

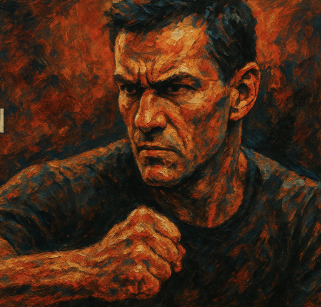

“It is time to put character and resilience back at the heart of what we offer young people – how to persevere when things get tough, how to manage anger, anxiety and low mood, and how to learn from setbacks and failure.”

“We will not only halt the spiral towards crisis, but cultivate much needed grit amongst the next generation”

There’s nothing wrong with teaching resilience. But if you work with young people today, you know the problem isn’t a lack of character. It’s the sheer weight of what they’re expected to carry. The stress they’re under is constant – and much of it comes from living in a digital world that adults didn’t grow up in and often don’t fully understand.

Telling young people to manage “anger, anxiety and low mood” without looking at what’s causing those feelings is like handing them a bucket and ignoring the flood.

The kind of pressure we didn’t have

Teenagers today are dealing with things that would have been unimaginable to most of us at their age. Comparison, visibility, pressure to perform – all of it online, and all of it endless. A friendship issue used to end when you got off the bus. Now it follows you home on your phone. A mistake used to fade with time. Now it lives in screenshots.

We hear a lot about “grit”, but not much about why they might feel ground down in the first place.

Teaching young people to push through is fine – but only if we’re also helping them understand why they’re feeling overwhelmed, and doing something about it.

So have we ‘lost’ our grit?

It’s no accident that Labour chose the Telegraph as the place to introduce their focus on “grit”. It’s a word that resonates in a very particular way with an audience steeped in the belief that things were tougher – and somehow better – back in the day. And sure enough, responses to the article captured that tone exactly.

One reader commented:

“It’s funny, we used to have it, ‘grit’ although it wasn’t called that. We learnt it from the slings and arrows of life, peer groups, teachers who taught and woe and behold if you didn’t behave, organisations like the scouts and guides and a general unspoken understanding that you were being prepared to meet life.

Then along came ‘trendy’ teaching, you no longer had to sit at a desk and keep quiet, ‘six of the best’ by the headmaster was considered to be assault and the aim was to make things easy for the pupils, to be their friend instead of their teacher and spelling, grammar and discipline were no longer necessary.

And, good heavens, ‘grit’ went out the window and ‘mental health’ flew in.

I don’t suppose there could be a connection there somewhere, could there?”

It’s a telling view – not because it lacks honesty or feeling, but because it speaks from a world that doesn’t exist for many young people today.

Yes, there was resilience in the past. But the shape of childhood has changed. What young people are being asked to navigate now – especially online – is more constant, more invasive, and often more performative. They’re not being soft. They’re surviving a system that’s infinitely more complex than the one many adults remember.

A different way to think about resilience

When we think about “grit” and the connection to “being resilient”, it’s often portrayed as a personal trait – something you’re either born with or you’re not – and if you don’t have it, you need to find some. But psychological research offers a different perspective. The American Psychological Association describes resilience not as toughness, but as “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress.” That’s something we grow, not something we grit our teeth and summon.

In my work with young people, I teach a version of resilience that’s less about powering through and more about knowing what you can rely on. Not just in yourself, but in the world around you. Real support. Real connection. Real values. These are the things that help young people stay grounded, especially when so much of their day-to-day experience feels weightless, performative, or out of their control.

When we talk about resilience in schools, it’s not a motivational slogan. It’s a conversation. It’s about recognising that part of being human is knowing who you can turn to, how to ask for help, and where your sense of self truly comes from. And in a world that’s often more digital than real, teaching young people what is real – and what they can trust in – is one of the most important things we can do.

Leave a Reply